Historical Facts

The following information comes from the 2001 Race Riot Commission Report:

Black Tulsans had every reason to believe that Dick Rowland would be lynched after his arrest. His charges were later dismissed and highly suspect from the start. They had cause to believe that his personal safety, like the defense of themselves and their community, depended on them alone. As hostile groups gathered and their confrontation worsened, municipal and county authorities failed to take actions to calm or contain the situation.

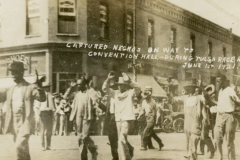

At the eruption of violence, civil officials selected many men, all of them white and some of them participants in that violence, and made those men their agents as deputies. In that capacity, deputies did not stem the violence but added to it, often through overt acts that were themselves illegal. Public officials provided fire arms and ammunition to individuals, again all of them white. Units of the Oklahoma National Guard participated in the mass arrests of all or nearly all of Greenwood’s residents.

They removed them to other parts of the city, and detained them in holding centers. Entering the Greenwood district, people stole, damaged, or destroyed personal property left behind in homes and businesses. People, some of them agents of government, also deliberately burned or otherwise destroyed homes credibly estimated to have numbered 1,256, along with virtually every other structure — including churches, schools, businesses, even a hospital and library — in the Greenwood district. Despite duties to preserve order and to protect property, no government at any level offered adequate resistance, if any at all, to what amounted to the destruction of the Greenwood neighborhood. Although the exact total can never be determined, credible evidence makes it probable that many people, likely numbering between 100-300, were killed during the massacre.

Not one of these criminal acts was then or ever has been prosecuted or punished by government at any level: municipal, county, state, or federal. Even after the restoration of order it was official policy to release a black detainee only upon the application of a white person, and then only if that white person agreed to accept responsibility for that detainee’s subsequent behavior. As private citizens, many whites in Tulsa and neighboring communities did extend invaluable assistance to the massacre’s victims, and the relief efforts of the American Red Cross in particular provided a model of human behavior at its best. Although city and county government bore much of the cost for Red Cross relief, neither contributed substantially to Greenwood’s rebuilding, in fact, municipal authorities acted initially to impede rebuilding.

Despite being numerically at a disadvantage, black Tulsans fought valiantly to protect their homes, their businesses, and their community. But in the end, the city’s African-American population was simply outnumbered by the white invaders. In the end, the restoration of Greenwood after its systematic destruction was left to the victims of that destruction. While Tulsa officials turned away some offers of outside aid, a number of individual white Tulsans provided assistance to the city’s now virtually homeless black population. But it was the American Red Cross, which remained in Tulsa for months following the massacre, that provided the most sustained relief effort. Maurice Willows, the compassionate director of the Red Cross relief, kept a history of the event (available in full under the “Documents” section of this online exhibit).